«FRATELLI TUTTI»?

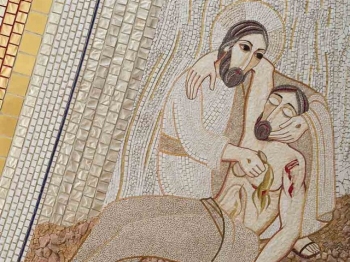

Fratelli tutti, n°66: «Let us look to the example of the Good Samaritan. Jesus’ parable summons us to rediscover our vocation as citizens of our respective nations and of the entire world, builders of a new social bond.» (The Good Samaritan, detail of a mosaic by Father Rupnik, the Blessed Sacrament Chapel of the Cathedral of Saint Mary the Royal of La Almudena in Madrid. ©Centro Aletti – LIPA Edizioni)

Fratelli tutti, n°66: «Let us look to the example of the Good Samaritan. Jesus’ parable summons us to rediscover our vocation as citizens of our respective nations and of the entire world, builders of a new social bond.» (The Good Samaritan, detail of a mosaic by Father Rupnik, the Blessed Sacrament Chapel of the Cathedral of Saint Mary the Royal of La Almudena in Madrid. ©Centro Aletti – LIPA Edizioni)

"If the conviction that all human beings are brothers and sisters is not to remain an abstract idea (…) then numerous related issues emerge" (FT 128).

The first of these challenges is to understand if and why we are all brothers and sisters. Faced with daily wars, hatred of all kinds, past and present, terrorism, personal and collective wickedness, one wonders if and how one can speak of fraternity; a word that has also given rise to ideological and political misunderstandings and the French Revolution itself of the eighteenth century made it a cornerstone of the “new” era; an era in which violence, racial segregation, colonialism, war and, subsequently, the exploitation of labour, the birth of complex ideologies of domination and supremacy (nazism, communism and dictatorships of various inspiration) were not spurned.

For Christ and for the culture that originates in him, fraternity has another history - the biblical one – which is profoundly human and existential, and does not ignore the assertion of homo homini lupus (maxim derived from Plautus' Asinaria, II, 4, 88), which was intended to explain human selfishness and to designate the condition in which men fight each other to survive.

The vision – a truly novel one - that Jesus traces is “other”. And it is in this perspective that the expression removed from the Admonitions attributed to St. Francis must be understood, who asked his brothers to look to Christ to grasp the sense of fraternity he wanted among them.

Biblically speaking, the idea of fraternity (prior to any form of brotherhood which has a somewhat curtailed and seemingly comradely flavour) arises not simply from sharing the same biological maternity / paternity, but from the overcoming of the biological aspect well expressed existentially by Psalm 51, which he confesses: "sinful from the time my mother conceived me" (v.5). For the same Psalm, the human being is aware that in life he becomes the companion of thieves and adulterers, of fomenters of deceptions, and might even kill his own fellow man in the greatest contempt of God (cf. 16 et seq.). A bad conscience almost leads Cain to bluff the Eternal One, trying to call himself out of the brotherhood of Abel; this story continues in humanity. Instead, we carry original sin (now almost discarded in contemporary theology and preaching) with us. Moreover, without it, we cannot receive baptism from above (cf. John 3: 3-8), according to the teaching of Jesus to Nicodemus: he intended to understand what was the "newness" preached by Christ; nor would there be a role for that "Lamb of God ... who takes away the sin of the world!" (John 1:29), Jesus, whom John the Baptist pointed out when he saw him coming towards him.

What was this novelty? Jesus was teaching the crowds and disciples the heart of relationships with God, with society (including religious) and with others; then he firmly affirms: "You are all brothers" (Mt 23: 8). Here it was not meant simply because of the common Jewish identity; He was widening his gaze, since "there is only one Father, and He is in heaven" (Mt 23: 9). Thus with Jesus the question becomes transcendent. Fraternity - says Jesus - originates from the heavenly Father and, for this reason, overcomes all discrimination relating to the colour of skin, culture and traditions; origin which, even in the ecclesial sphere, seems to be downgraded or ignored. If the appeal to transcendence were to fail, fraternity would shatter; equality would not resist various pressures, including economic and social ones, and freedom would selfishly lock itself in on itself. Fraternity has a transcendent significance. The papal encyclical also recalls this, citing John Paul II's Centesimus Annus (cf. FT 273).

A further challenge arises: if transcendence were true, what God are we talking about? The question was posed to me in a simple but profound way by a Christian who lived in Iran at the time of my service in that country and who had to continually confront himself with the “God of Islam”: “Is the God of Jesus Christ - he said not without perplexity - the same as the God preached by Muslims?”. It was a pertinent question. The concrete contradictions, the fact of being called “unbeliever/kāfir”, were/are real. Abu Dhabi, for relations between Christians and Muslims (Document on Human Fraternity for world peace and living together, February 4, 2019) is a new step, at least not to make war and not to create more humanitarian crises. Terrorism and extremism are against Abu Dhabi. But the hope that the Abrahamic root of the three monotheistic religions, of which the Second Vatican Council speaks (cf. LG 16), can bear fruit has not withered. Therefore, in this context it should not be risky to think that the Abraham Accords (between United Arab Emirates, Bahrain and Israel and possibly others in the near future) is an initiative that could imply previously inconceivable consequences at a diplomatic as well as economic, cultural and religious level. Emerging from the logic of conflict means thinking differently and at a higher level.

When Jesus speaks of the "heavenly Father" he certainly refers to the God of Abrahamic revelation. He did not speak of an abstract or philosophical God; to the Samaritan woman (remember that there was no good blood between Samaritans and Jews!) who asked him which God should be worshiped, Jesus replies by going beyond the issue of the nearby Mount Gerizim on which the Samaritans worshiped “their” God, but also the mountain of Jerusalem on which the Jews worshiped the Most High. Instead, Jesus speaks of a "Father" who wants to be adored "in the Spirit and in truth, for they are the kind of worshipers the Father seeks. God is spirit, and his worshipers must worship in the Spirit and in truth” (John 4: 23-24). This God is then revealed by / in Jesus Christ, the Messiah, whom we can no longer leave out of consideration. Without him we return either to pantheism or to the irenic-theosophical divisions of a God with a Platonic or esoteric flavour. The God of Jesus Christ has the characteristics of the Father who in the Son illuminates, redeems, reconciles us and on the cross opens us up to fraternity. But which?

To remove any further misunderstanding, to the Doctor of the Law who asked for explanations, Jesus tells the splendid parable of the good Samaritan (cf. Lk 10: 25-37); there is no theory, but exemplification, and above all that powerful one: "Go and do this too" (Lk 10: 37); Pope Francis's encyclical illustrates with undoubted clarity this parable which represents the theological heart of Jesus' teaching on fraternity and is at the centre of the pontifical document (cf. nn. 56 et seq.). The parable - the Pope explains - highlights the trust “in the best of the human spirit" (FT n. 71) which takes shape and originates in truth.

In truth? Once again, the Christian thinks of Christ: "I am the way, the truth and the life" (John 14: 6). In understandable terms, we say that Jesus perfects his teaching for us, so to speak, by speaking of the most difficult human acts, such as (cf. Mt 5: 20 et seq.) revenge ("But I tell you, do not resist an evil person ... ": Mt 5: 39), human relations (" ... If anyone forces you to accompany him for one mile, go with him two miles": Mt 5: 41), the attitude towards those who are in need ("and do not turn away from the one who wants to borrow from you": Mt 5: 42) or the relationship with an adversary (" ... If my brother commits sins against me, how many times will I have to forgive him? Up to seven times? ... I tell you, not seven times, but seventy-seven times": Mt 18: 21-22). Pay attention! - Jesus says - a certain interested fraternity could exist also between the "tax collectors" and the "pagans", but for a Christian fraternity has "your heavenly Father" as a reference (Mt 5: 48)!

The fraternity of which Jesus speaks, therefore, cannot be reduced simply to an anthropological or sociological datum; for the Christian the question is theological, transcendent (cf. FT 85); that is, it needs God the Father, the principle point of reference and keystone of all fraternity. Without God the Father, fraternity goes into crisis and continually needs props: tolerance, pacts, norms, judgment, strength. Reason alone cannot establish fraternity (cf. FT 272).

Jesus, as a Master, is the guarantee of a vision that transcends the anthropological limit in itself. Mother Teresa of Calcutta, speaking to a nun who wanted to leave the Congregation because she could no longer bear the stench of the poor, asked who was that poor man whom she had picked up that day: “Didn't he have the face of Christ?”, she asked, and the nun remained in the Congregation. “For Christians - says the Pope -… recognizing Christ himself in every brother” (FT 85) allows us to overcome the many motivations and questions that ensnare us. This calls into question the third of the theological virtues, charity, which warms every relationship. Charity goes far beyond any sociological or biological dimension; it has its seat in a God to be loved "above all things for oneself, and neighbour as ourselves for love of God" (CCC 1822); charity is fulfilled in Jesus who loved his own to the end (cf. John 13: 1).

The Letter to the Hebrews goes into an interesting explanation about the humanity assumed by Christ, commenting splendidly "it was fitting" (decèbat, éprepen) (Heb 2:10) the redemptive incarnation of Jesus, "he who sanctifies" and "he is not ashamed of calling us brothers” (Heb 2:11).

One last challenge: Are we all brothers and sisters, but “different” brothers and sisters? Yes. Diversity does not undermine the social sense of existence or the conviction of the dignity of each person, nor does it affect the dimension of spirituality (cf. FT 86). Diversity promotes human wealth and beauty. In other words, let us think of a diversity not of a generic philanthropic or universalistic flavour, but the creator of a true form of social “friendship” which generates, through righteousness of heart, truth, the common good and peace.

Fernando Cardinal Filoni

(December 2020)